- The EU Commission has officially announced its intention to replace the 2035 full ICE ban with a new regulation requiring a 90% reduction in fleet‑wide CO₂ emissions from 2035 onward.

- The revised framework reopens the market for transitional technologies such as PHEVs and EREVs, which now play a renewed strategic role in meeting future CO₂ targets.

- China holds a consolidated lead not only in BEVs but also in PHEV and EREV technologies, and with their OEMs accelerating their expansion into Europe, the new regulatory landscape may unintentionally reinforce their competitive position.

The European automotive landscape is undergoing a significant policy shift. The European Commission has announced a proposal to scrap the previously approved 2035 ban on new combustion‑engine vehicle sales, replacing it with a requirement for automakers to reduce fleet‑wide CO₂ emissions by 90% from 2035 onwards.

This marks a recalibration of the EU’s decarbonisation strategy, driven by mounting industrial pressures and intensifying global competition.

Why the EU is changing course

Originally introduced as a cornerstone of the EU’s climate strategy, the 2035 ICE ban aimed to accelerate the transition toward fully zero‑emission mobility. However, the regulation has always included the possibility of a reassessment and potential revision, scheduled for 2026.

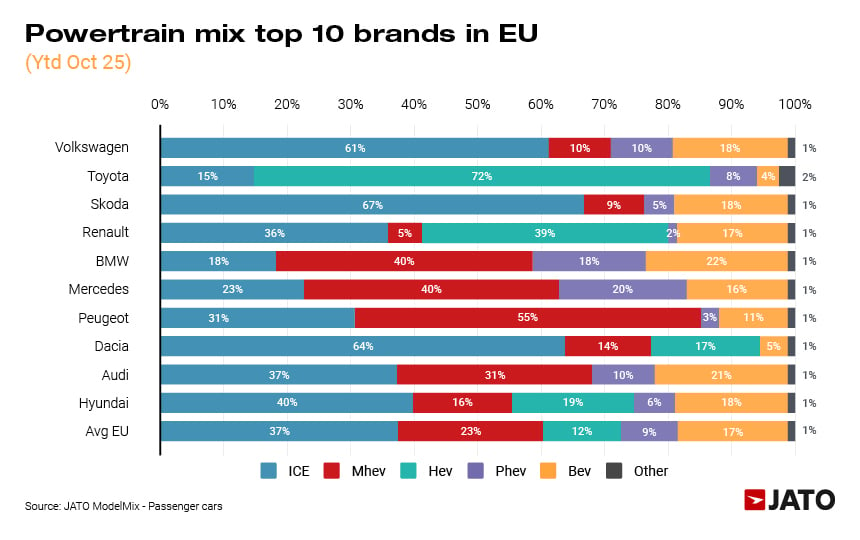

In recent years, several OEMs, including Volkswagen, Stellantis, BMW, and Mercedes, have openly challenged the regulation, supported by key European governments such as Italy and Germany. Their concerns focus on the region’s readiness for such a rapid transition, noting that customers remain strongly oriented toward conventional powertrains (as of YTD October 2025, more than 60% of new passenger cars registered in the EU are still ICE or MHEV).

They also argue that the ban could provide an advantage to the upcoming wave of Chinese brands, given that the country is currently the world’s largest EV market, where two out of every three BEVs sold globally are purchased.

On the other side, more than 200 companies, including Volvo, Lucid, A2A, Erg, Uber, and others, have formally urged the EU to maintain the original transition timeline. Their stance is also supported by several member states, including Spain and the Nordic countries.

Now, even before 2026, the EU Commission has already acted proposing a review of the rules, introducing a 90% emissions‑reduction mandate instead of a complete phase‑out. This approach offers manufacturers greater technological flexibility, keeping the door open to synthetic fuels, hybrid solutions, and other transitional technologies.

To maintain carbon neutrality, the proposal also includes the need to compensate for the remaining 10% by using EU‑produced green steel or climate‑neutral fuels such as e‑fuels and biofuels.

Is this really an advantage over newcomers?

Focusing on Passenger Cars, one major implication of the revised framework is the renewed viability of hybrid and ICE powertrains. However, considering 2021 as the baseline year for the 90% reduction, the new target would be around 11 g/km. Based on current CO₂ emissions by powertrain type, the technologies expected to expand in order to remain compliant with the regulation are:

- BEV: expected to take the majority of the market share, as they are the only technology capable of fully offsetting other emissions thanks to their 0 g/km CO₂ value.

- EREV (Range‑Extender): currently the second technology with the lowest emission levels; however, at around 30 g/km CO₂, it still requires BEVs to offset the remaining emissions.

- PHEVs: expected to remain a limited‑mix option, especially as their certified emissions have recently been revised upward under Euro 6E‑bis.

All other powertrain technologies appear to remain exposed under the new regulatory environment. Among them, full hybrids (HEVs) continue to be the most efficient and market‑ready solution, with best‑in‑class models, such as the Toyota Aygo X, achieving combined‑cycle emissions as low as 85 g/km of CO₂, still requiring the equivalent CO₂‑offset of at least seven BEVs for every single vehicle.

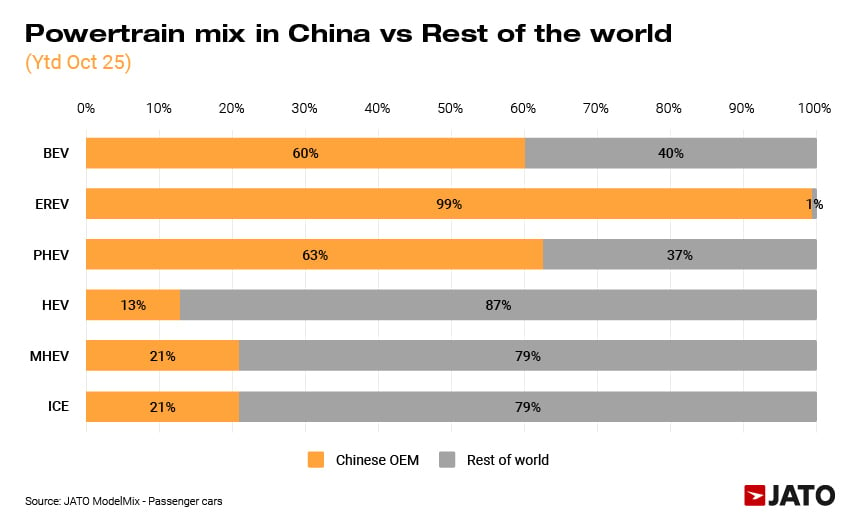

The question, however, is whether this change genuinely favours European automakers. China’s leadership is not limited to BEVs; it extends to PHEVs, where the country accounts for 63% of global volumes, and to EREV technologies, where the country accounts for 99% of global sales. This means that by reopening the regulatory door to these solutions, Europe is focusing on powertrains where Chinese OEMs already enjoy a clear and consolidated technological advantage.

A deeper analysis by technology

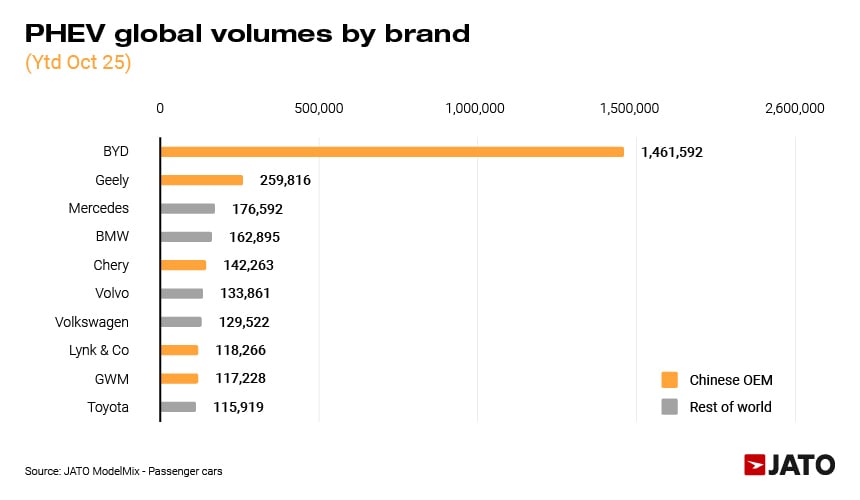

A closer look confirms this gap. In the PHEV powertrain, BYD is by far the largest global producer, with nearly 1.5 million units registered in the first ten months of 2025, followed at a distance by Geely with around 250,000 units. The first European brands appear only in third and fourth place, with Mercedes and BMW respectively; and considering that Volvo has been part of the Geely Group since 2010, European representation in the global top ten of PHEV sellers is limited to just two brands.

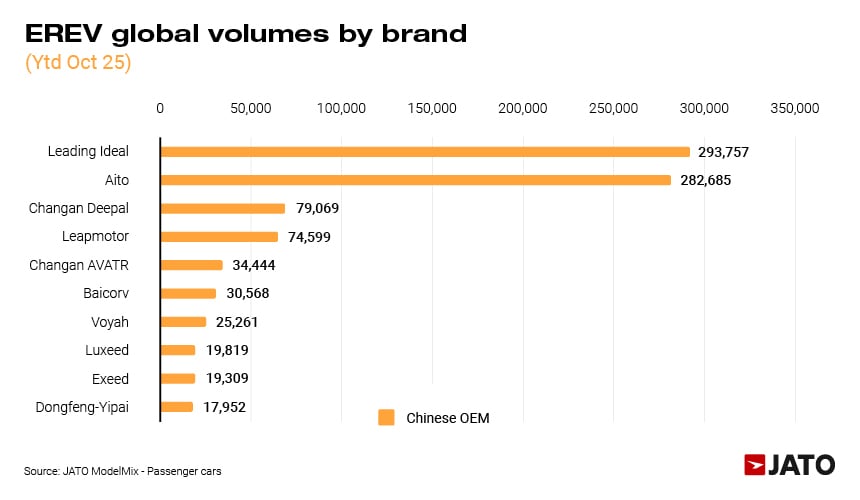

The gap is even more evident in the EREV powertrain. This is fundamentally a Chinese‑led technology, with almost all global volumes concentrated in China. In Europe, the only manufacturer operating at scale so far is Leapmotor, supported by its joint venture with Stellantis.

Since 2020, when the first Range Extender had been introduced in China, this powertrain share has grown consistently in the country, giving Chinese newcomers approximately a five year technological head start. Several European OEMs, including BMW and Volkswagen, have announced plans to introduce EREV powertrains, but it remains unclear whether they will be able to close the gap sufficiently.

At the same time, the growing attention around this technology may simply smooth the entry path for leading Chinese players such as Li Auto, AITO, Deepal or Avatr, all of which are beginning to expand towards Europe.

Conclusion

With the new regulation now in force, the EU has proposed a more flexible and pragmatic approach to decarbonisation, easing immediate pressure on European manufacturers. Allowing ICE, hybrid and extended‑range technologies back into the compliance pathway offers short‑term relief and more realistic planning horizons for OEMs still navigating slow BEV adoption and significant industrial constraints.

However, this shift also introduces strategic risks. The technologies now central to meeting the revised targets, PHEVs and especially EREVs, are precisely those where Chinese OEMs already hold a strong technological and industrial lead. As Chinese brands accelerate their expansion into Europe with mature and competitive electrified powertrains, they could benefit disproportionately from the new framework.

To mitigate this risk, the European Commission has also proposed a €1.8 billion ‘Battery Booster’ programme to accelerate the development of a fully EU‑based battery value chain, along with reduced red tape and stronger enabling conditions for the transition. However, some manufacturers, such as Stellantis, have already stated that while this represents a positive step in addressing the region’s transition challenges, it remains insufficient.

The key challenge for European manufacturers will be to use this regulatory flexibility not merely to postpone the transition, but to rebuild competitiveness in powertrains where they currently lag. Failing to do so risks creating a scenario in which the revised policy unintentionally strengthens the position of their fastest‑growing global competitors.

Arrange a consultation today

Speak to a member of our team to discuss your requirements and find out how our bespoke consultancy solutions can help you meet your strategic goals.